MEDITATIONS: I CHING; THE BOOK OF CHANGES, CANTO SEVEN

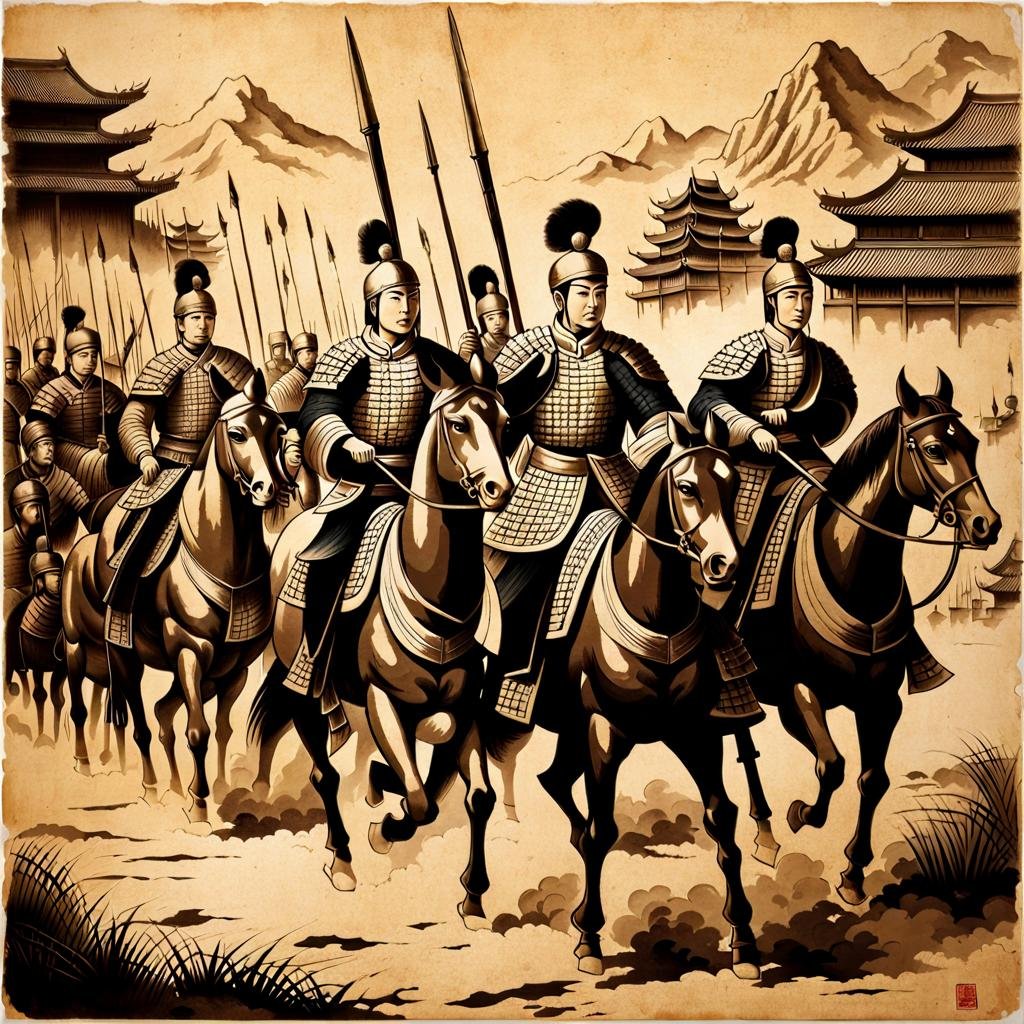

Multitude—Teacher—Society |or| The Army

Look for an opportunity to re-order those parts of your life that are important to you. Above all, be disciplined and organized at the start of any journey or endeavor. Be wary of inept leaders and govern yourself according to your higher ideals. (Bright-Fey 43)

For the army to be right, mature people are good; then there is no fault.

Yin 1: The army is to go forth in an orderly manner; otherwise, doing well turns out badly.

Yang 2: In the army, balanced, one is fortunate and blameless. The king thrice bestows a mandate.

Yin 3: It bodes ill for the army to have many bosses.

Yin 4: The army camps; no blame.

Yin 5: When there are vermin in the fields, it is advantageous to denounce them; then there will be no fault. A mature person leads the army; there will be bad luck if there are many immature bosses, even if they are dedicated.

Yin 6: The great leader has a command to start nations and receive social standing; petty people are not to be employed. (Cleary 28-34)

The multitude which teaches people how to properly form a society is symbolically represented by an army. Armies are individuals banded and bonded together under the directive of a leader who himself is second-in-command to a greater sovereign. Armies are disciplined and, when employed for their intended purposes, are meritocratic institutions.

Thus is “The Army” hexagram formed by the trigrams water inside and earth without. Within, one is endangered by the passions; yet without, one is yielding and receptive. That is the role of the soldier. Where the prior canto, “Contention,” focused on a “son of heaven,” one born and cultivated for a position in leadership, “The Army” advises the masses via describing the proper conduct and organization of a military force—the principles about which are applicable to any social institution or even an individual.

For instance, the first Yin emphasizes the need for “mature people.” Those who are mature are those who think and act in accord with their purposes. They are human beings in possession of wisdom obtained by means of direct experience with the world. They are those whose values are properly hierarchically arranged. They can discern vice from virtue, and therefore they are necessary when organizing troops, business partners, or even oneself. Without them, it is very likely one or even many will miss the mark. With them, long foreseen obstacles can be avoided.

The second Yang is more complicated. It is the only Yang in the hexagram, and its middle position places it as the internal or subjective correspondent to the middle, fifth Yin—which is in the position of leadership. Given that it is balanced, both by its central position and its fifth Yin pair, it can be interpreted as referring to the voluntary subordination of the ego to a just and competent commander: it is the Yang leading the Yins, much like the conscious leading the unconscious instincts—though it leads, it must do so in accord with the mandates of Heaven, for the ego is a thing of the Earth, a product of the Great Course and not the other way around.

In short, though one consciously directs decides his path, he is not just a leader but also a follower. His accord with reality and subordination to those more mature results in good fortune more often than not.

The third Yin warns about a failure of the second Yang to manifest. It is best for the self or an organization to be integrated, that is to say, integrous—to have integrity under a consistent and coherent set of values. This is not the case when multitudinous wills or instincts order the others or the self in many directions simultaneously. That, as in an army, is sure to lead to confusion and defeat.

Moving toward the external, “the army camps,” describes the proper times for a person or company to wait or even retreat. In an army, such commands are understood to be necessary if victory is to be obtained. However, in general life, forestalling progress or advancement is often associated with failure. This should not be the case. There are times when the mature thing to do is to “wait on the sand” and avoid contention, for to advance when one does not have the advantage is to bring about one’s own defeat.

The fifth Yin speak about just the opposite. There will come a time when a real grievance or trouble justifies or even obliges people to act in reprisal. When one’s lands are under threat by invaders, then it is proper to follow a mature leader in contention. However, maturity is key. Dedication and fervor are not the same as wisdom and righteousness. If one is disintegrated, pulled in many directions by the instincts, then though he may get lucky from time to time, mostly he will meet with disaster even if his act is justified.

The top Yin is a warning. Even when there is a wise and mature leader, a plethora of petty, bitter, incompetent people will spoil his command. Those who are bad fruit ought to be cut from the tree: lazy and dishonest employees should be fired, and aspects of the self which lead oneself astray ought to be dishabituated.

Great change is possible, both at the level of the individual and of the society, but this can only be accomplished by the voluntary receptivity of the people under wise command. In this way, self and society are likened to an army: obedient soldiers who choose their generals wisely will prevail.

I Ching; The Book of Changes, with commentaries by Cheng Yi, translated by Thomas Cleary, Shambala Library, 2003.

I Ching: The Book of Changes; An authentic Taoist translation, translated by John Bright-Fey, Sweetwater Press, 2006.