MEDITATIONS: I CHING; THE BOOK OF CHANGES, CANTO FORTY-ONE

Condense—Lessen—Quell

|or| Reduction

It is best to give up any hard-lined opinions that you might have. Find a compromise position and middle path, particularly when encountering the problems of others. Observe events with an eye toward maintaining an overview of salient facts. Avoid crowds and over-stimulating circumstances. (Bright-Fey 111)

Reduction with sincerity is very auspicious. If it is possible to be truthfully steadfast without error, it is beneficial to go somewhere.

What is the use of two sacrificial grain containers?

They are to be used for offerings.Yang 1: Having done the task, go right away and there will be no blame. Assess reduction.

Yang 2: It is beneficial to be correct. An expedition bodes ill. Do not reduce, and you benefit.

Yin 3: When three people travel together, they lose one person. One person traveling gets a companion.

Yin 4: Reducing the sickness, do it quickly and there will be joy, without blame.

Yin 5: Some help here, ten companions; even auguries cannot gainsay them. Very auspicious.

Yang 6: Do not decrease, but increase it. That is blameless. It bodes well to be correct. It is beneficial to go somewhere. Getting subjects, one has no house. (Cleary 246-254)

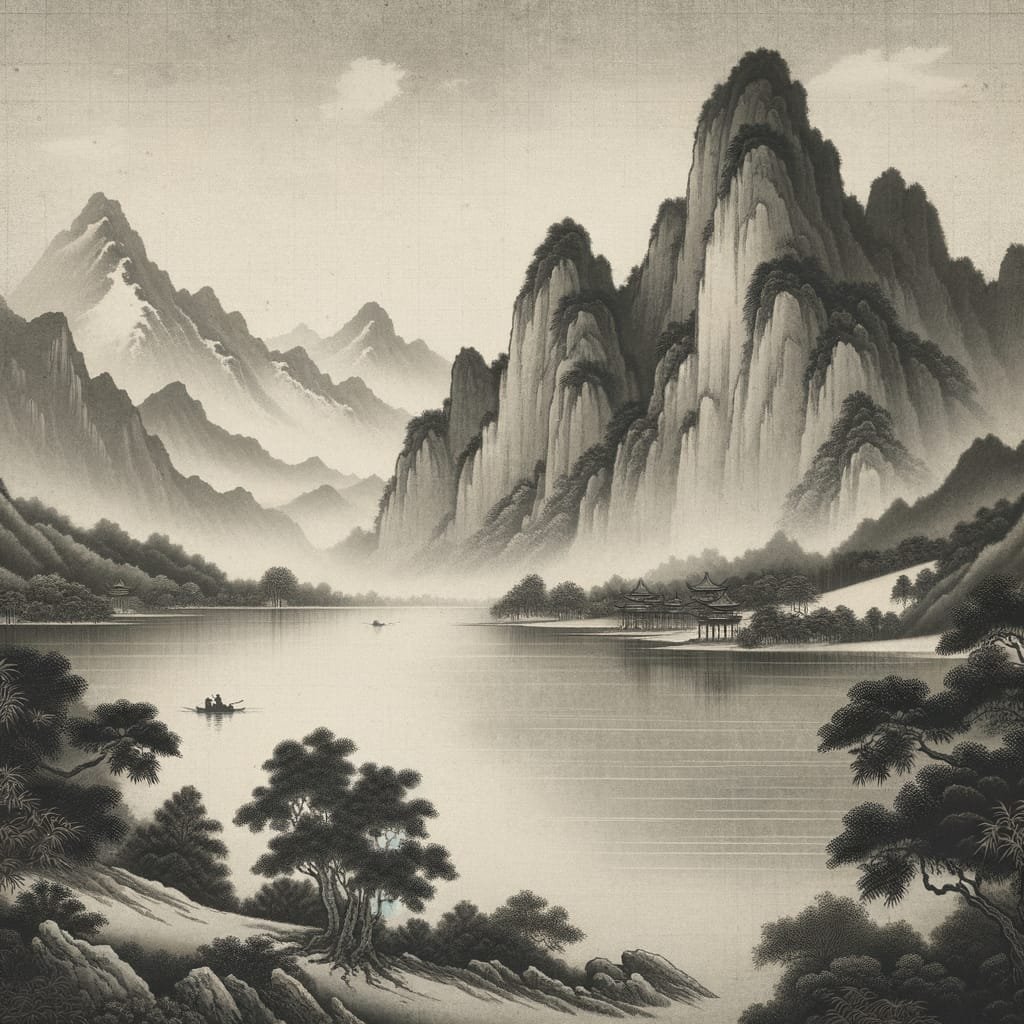

The image is that of a lake at the base of a mountain. The deep roots of trees feeds from the underground ravines themselves nourished by the lake. This is the case in spite of the separation. The mountain reaches high and the water of the lake seeks to be low. Yet still, a sacrifice is made by those below for the sakes of those above that the solution of the prior hexagram may be carried out: it is this dynamic, the necessary sacrifice by the common folk in order to allow those above to bring about a better future, which is known as Reduction—in opposition to gain; for to gain is the correspondent of reducing, gaining being when those below benefit from the actions of those above.

These are perhaps difficult concepts for a modern westerner, especially a modern American to accept. Here, the I Ching speaks of an assumed hierarchy of human potential, ability, and station. It also assumes a proper yet inequal reciprocal relationship between these two stratifications of human being. There will be those above with privileges that accompany their duties, and there will be those below who, lacking such duties and responsibilities, also lack the freedom of those above them.

When the Taoist translation speaks of surrendering rigid opinions and being willing to compromise, it is speaking primarily to those below. During a time of reduction, those with little will have to give up much in order for their children to have more than they had. This is the sacrificial offering mentioned in the Confucian translation, and when such a sacrifice is made sincerely, without resentment and bitterness, it can come to fruition in the near future.

The first Yang elaborates on the details of what one’s proper attitude should look like. Those at the bottom should not seek praise or glory or even reward. During a time of reduction, the lowly should toil and sacrifice in silence, completing their tasks and moving forward to the next ones. Progress will be made, but only if the spirit endures; and the spirit can only endure if it voluntarily takes on the wight of the world in order to elevate future generations on giant shoulders.

The second Yang is firm in a balanced position in the body of joy, and he represents the proper limits of self-sacrifice. The lowly will need to reduce, but they only have so much to give. The offerings of the low to the high should stop where those below can still be happy and find meaning in their lives. In this way, it is balanced for the lowly to be firm and resolute so long as they are also sincere and genuine. They have paid their contribution to the solution, and in so doing have helped the fifth Yin, the weak leader, to bring forward a better society.

The third Yin represents the transfer of active and creative energy from those below to those above. One can imagine this hexagram as Heaven below and Earth above—three Yangs below three Yins. To form Lake below and Mountain above, one must give Earth the final Yang from Heaven. This is the three travelers losing one companion who becomes the sole traveler of the second party.

The fourth Yin corresponds to the first Yang but applies to those above as opposed to those below. However, the rule is just the same. The benefactors of the sacrifices of the lowly have a duty to act quickly in the implementation of the solution to societies problems. They should not be tempted by lethargy, nor should they wait for the sake of glory or advantage. Their position is justified because of the balance of duties and responsibilities. Propriety rests on that balance, as does the goodwill of those who gave. Failure to act quickly will result in resentment and eventual revolt.

The fifth Yin, having been given the proper help by the second Yang, cannot fail in the implementation of the solution. Because the second Yang knew when to stop, there will be no infighting, and therefore those above and those below will act in unison. Such a harmony looks and feels like an inevitability, so much so that no one even thinks to consider failure a possibility. This is a kind of faith born from the voluntary acceptance of the necessity and virtue of reduction; and it is the kind of faith that ennobles a people and makes them virtuous.

The willing transfer of creative energy from the third Yin to the sixth Yang is the culmination and end of reduction. Once the sacrifices have been made and duties fulfilled, it is no longer time to reduce but to expand. That is why the sixth Yang says, “Do not decrease, but increase it.” The purpose of the reduction was to make fertile the ground for this moment, the birth of a new era more bountiful, virtuous, and harmonious than the last—harmonious in that “one has no house” despite the presence of subjects. When each acts in accordance with his proper role, the division of hierarchy seems to vanish, as everyone finds joy in his place in the universe.

I Ching; The Book of Changes, with commentaries by Cheng Yi, translated by Thomas Cleary, Shambala Library, 2003.

I Ching: The Book of Changes; An authentic Taoist translation, translated by John Bright-Fey, Sweetwater Press, 2006.