MEDITATIONS: I CHING; THE BOOK OF CHANGES, CANTO FIVE

Patience—Rain—Waiting

|or| Waiting

Look for a time to take stock of what you have and where you are going. We are all a collection of gifts and deficits and will act accordingly. Be aware of the difficulties that you encounter without succumbing to them. Be careful; danger is approaching. (Bright-Fey 39)

When there is sincerity in waiting, light comes through. Correctness leads to good results. It is beneficial for crossing great rivers.

Yang 1: Waiting in the outskirts, it is beneficial to be constant; then there is no fault.

Yang 2: Waiting on the sand, little is said; the end is auspicious.

Yang 3: Waiting in the mud brings on opposition.

Yin 4: Waiting in blood, coming out of one’s own lair.

Yang 5: Waiting with food and drink, it is auspicious to be correct.

Yin 6: Gone into the lair. Three people come, guests not in haste; respect them, and it will turn out well. (Cleary 18-22)

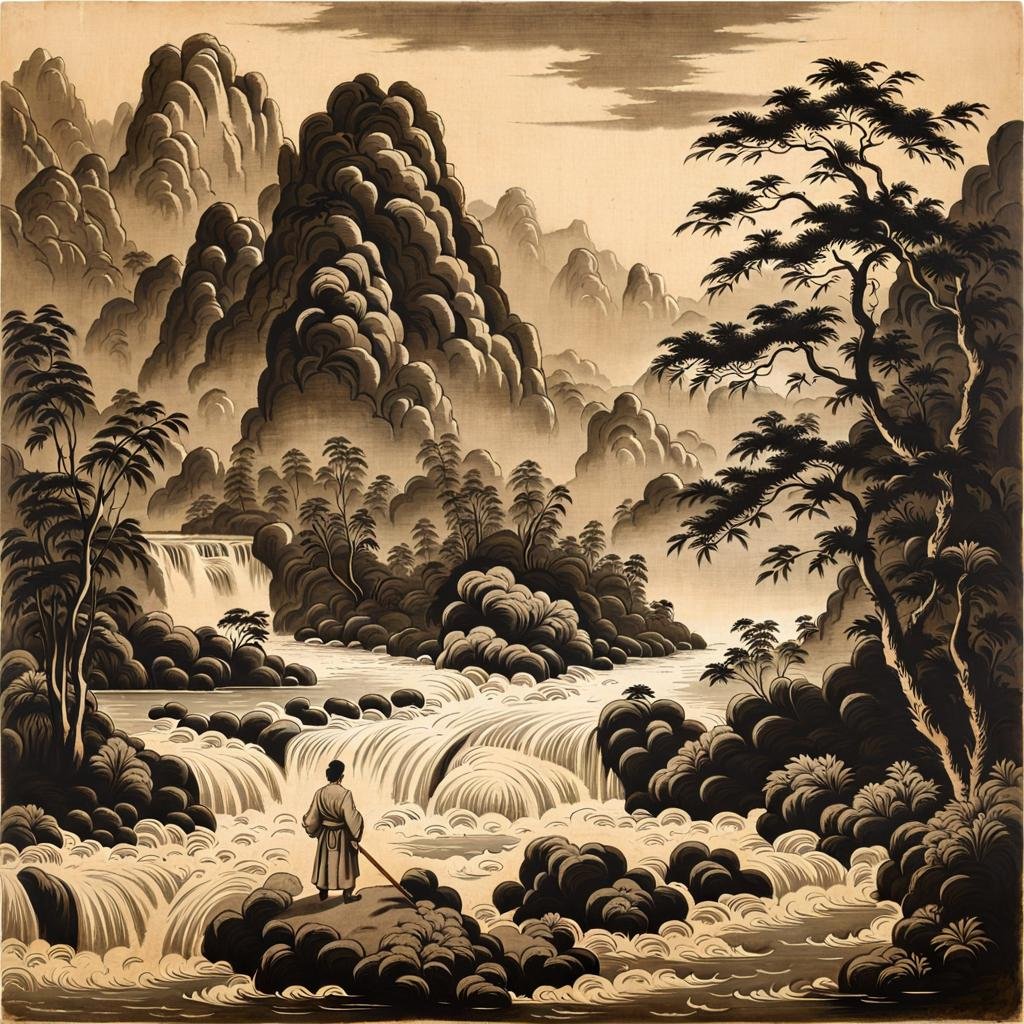

Even the most ambitious man at times will be made to wait. This is akin to being stuck indoors during a violent rainstorm or stopped suddenly by a wide, raging river. To initiate action prematurely, when heaven, those forces outside man’s control, is to ask for disaster. It is disharmony with the Way, discord where accord is what is needed.

During these times, one can wait well, or one can wait badly. It may be a strange dichotomy for the modern, western mind, but the difference results in eventual success or inevitable bloody catastrophe.

Waiting sincerely is taking the imposed down time as an opportunity to reflect and to attend to what one has been neglecting. Internally, this is the taking stock of creative potential. One verifies where his destination is and whether or not it is where it out to be. He rekindles his spirits and tends to his responsibilities. After all, either he will be perfectly ready once the river dies down, or else he shall be prepared to wade through it once he attains full moral strength.

“Waiting on the sand” is to keep the proper emotional distance from one’s desired end. While close to it, such as one is close to the water while standing on the strand, one does not obsess or become panicked. There will be difficulties and danger, but they have yet to arrive, and so the only proper thing to do is to tend to ones duties and prepare for that time. This is the opposite of “waiting in the mud.” The mud is too close to the danger ahead, too emotionally invested in an outcome yet to manifest itself. When one waits this way, he is likely to succumb to his weaknesses, because there won’t be anything he can do to achieve his ends, and his mind will be vulnerable instead of being preoccupied with attending to the matters at hand.

“Waiting in mud” will result in “waiting in blood,” that is, the distress that comes with not being able to manifest ones will and achieve one’s ends. Externally, such a person will not be able to find comfort anywhere or in anything. Good food will come to taste flavorless in his mouth, and his friends will seem no different to him than his enemies. He is wounded by his internal strife.

Better off he’d be if he gathered the proper provisions; the man who waits on the sand does so, and his wise course of action and perspective are rewarded once the right time finally comes.

This hexagram is heaven internally and water externally—that is the creative power oppressed by danger of the passions. When one waits properly, the creative impulse will eventually be released, and it will sustain itself thereafter. These are the three guests, the three Yangs, who come, once the danger has passed, to the sincere man who can now rest in the lair of his own success.

I Ching; The Book of Changes, with commentaries by Cheng Yi, translated by Thomas Cleary, Shambala Library, 2003.

I Ching: The Book of Changes; An authentic Taoist translation, translated by John Bright-Fey, Sweetwater Press, 2006.